tv Mosaic World News LINKTV November 26, 2012 7:30pm-8:00pm PST

7:32 pm

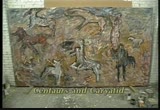

are you going to tour the exhibition? well, i've seen the show, you know. i think it looks good. well, it's certainly a grand theme. genesis. how can you beat genesis, right? [ laughing ] and the thing that you discover about it, it's interesting because you discover that, compositionally, the most difficult thing about the picture is not the figures, it's a tree. why is that? you have to find a place for it. if you have a pattern of some kind -- if you have no tree, then anything you do -- you can turn it upside down, lay it down, whatever, you know -- but a tree can only grow up. the only thing i'd say with genesis is the serpent or the snake because you can do anything you want with it. so wherever you feel there's some emptiness, put the snake in. and then find some empty place there, bring the snake there.

7:33 pm

you can put him anywhere, so that saves you. cheim: what do you think about the difference between figurative paintings and abstract paintings, and is there a difference at all? yeah. when you work where you have -- where you're not interrupted with an image, you're working completely free of the image, you can do anything at any time without stopping, without pausing to think of where it is, what's it doing. so a few years ago, when i put the figures in, i knew i was making it difficult. and i wondered how i would be able to handle that difficulty. but it's still about paint, mostly. i try not to lose sight of it, but, of course, people think that i'm trying to be funny with the figures, but i'm not. i think they become more real to me.

7:34 pm

resnick: something peculiar about artists... they have ups and downs. you climb, climb, climb, you're on a plateau, and for a while, whatever you do is just wonderful, or you think it is, and then you slide down it. if you're a good artist, you're going to go down. and it's up to you. and pulling yourself up again is the most importanpart of your life. it's getting out of the bottom that you put everything into yourself. that's when you change yourself

7:35 pm

to be the goddess that you'll be. you always carry the memory of the bottom and fear of the bottom. and when you start going to the bottom, it's panic. there are people who can't stand the panic. what happens then is that they begin to develop some kind of technique to keep out of that hole. once they do that, it's finished. they never go any further. they're done. what i want to do is get rid of this oil.

7:36 pm

and i'm ready to paint, but i'm not going to because i don't have the faintest idea what to do now. it's not in my head to do anything. i can't just go and move a brush around. i have to have a beginning. i don't want to just use models, figures. i just want to have some reason. and the beginning is adam and eve and a tree and a serpent and a garden, and that's enough, see. except that pat didn't like that kind of biblical con-- you know. and she said, "don't use adam and eve and creation. just say, 'you and me.'" and i liked that very much.

7:37 pm

i almost got that, didn't i, pat? passlof: yes. i can see just what i can do, and i could almost see the right thing to do. it wouldn't take much to get this started, huh? but, you know, i did this all in a couple of hours. the first five minutes is the best. [ laughing ] after that, you're in trouble. what am i going to do with these paintings? i have to think of something that will give me a start. i don't like the size of the figures. it's the wrong size.

7:38 pm

passlof: well, it's easy to cut them down. mm-mmm. i thought i could manage this size, and i now i see -- they are much larger than you usually do. yeah. and this, of course, is ridiculous. and that's ridiculous. absolutely ridiculous. the painting at the end? yeah i mean, it's... just aogance. just arrogance, thinking anything i do is fine. just arrogance. actually, behind that red figure, towards the right, you can see a little yellow. you see it? and that could be the head and the arm. much better than the figure in front. and there are even legs there, you know, underneath the arm.

7:39 pm

that figure could be much better than the red one. and with that idea, which i'll try to remember when i come to it, the whole painting can start. that's a start. and you can see i changed things. maybe i can reach it. i can't reach it. yeah, i can reach it. it sounds ridiculous to start a large painting with no plan, no sketch, no diagram, no composition. ah! nothing -- you're looking at a blank canvas,

7:40 pm

and you say, "what will i do?" so you make a brush mark. you have to find the beginning. now, i never intended to do anything like this. that's it. yellow, red, black, white -- they're useful tools, right? paint is a useful thing. so you need those different colors in order to kind of chop away at each other. the influence of the french school of painting -- van gogh and the impressionists -- was very strong in new york in the '30s. so everybody talked about color and matisse.

7:41 pm

if you're modern, you use color. well, first of all, color is expensive. but then on the other hand, i don't really know whether i like those very colorful blues and yellows and oranges. i knew an older artist who once lived in paris. one day i said to him, "can you tell me something about color?" he says, "there's one thing i can tell you -- nobody understands color." i said, "fine, that's just the way it is with me." and that was the end of that problem. around 1958, '59, somewhere around there, i started a painting. it was 18 feet by about 9 or 10 feet,

7:42 pm

and i'd never done a painting that big. and then i realized i didn't have the space to come back to see my painting. it was too close, and i couldn't seem to get far enough away to see what i'm doing. then my feeling about how i see a painting changed. i realized every time i do something, if i have to run back to take a look at it, it's impossible. i can't paint that way. ah! ah! instead of looking, i had to feel it. ah! in order to feel it, to work with it, i had to carry that feeling. well, a little more, little more, little more. it really made the biggest difference in my life as far as painting goes.

7:43 pm

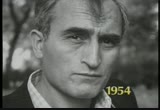

pat responds to something much more beautiful, much more rhythmic. i'm really not rhythmical or beautiful. i'm just like a different something. i fall. i-i keep from falling. i'm falling, but i keep from falling. that's me. pat is just the most beautiful. pat, who are these famous people? they're people from the museum. they're people from the museum? this sporty guy, who is he? looks like a collector. i'm sure he may be. i didn't meet pat till after the war, '49. passlof: '48. resnick: '48. passlof: i was studying with bill de kooning the summer before milton returned from paris. and bill thought of milton as his best friend and his most interesting artist friend, the person he could talk with most.

7:44 pm

7:45 pm

passlof: i'm, perhaps, overly romantic. you can see that the figures are moving, but i'm actually restraining myself. you can imagine what they would be doing. they would be flying off the paint if i wasn't. but i think intensity depends on restraint, preventing things from moving. and we all learned that a little bit inhe so-called abstract expressionist period when everything was going very fast. resnick: the difference between us -- i like to waste my paint. right. she never wastes her paint. i waste it. it's on the floor. pat can have a tube of color that she knows exactly what she's going to use it for. it's important to her, which is not for me.

7:46 pm

so her way of painting has to do with what she sees and how she uses it. passlof: i work abstractly in the beginning. i don't bring the figure or the horse or the tree into it. i find them in the abstraction, so it comes out of memory. you know, i'm a very good craftsman, so that part of it is the part i really don't want to call on. and so i just have ways of using large brushes that i can't draw well with. i'm deliberately undoing my color sense, my ability to draw. i'm tricking myself, in a way, so that what happens will be surprising to me.

7:47 pm

i'll tell you, this is a good story. max hutchinson gallery was showing the painting called "new bride," and the price was like $50,000 or something. now, there is a guy, melzack, he was a collector, and he said to me, "i want to buy that painting 'new bride,' but i'm not going to have anything to do with max." so this guy who had a store on grant street says, "i have this building which had been a synagogue, "and i want you to have it for a studio. i know you need a studio." so i said, "well, i would like to have it, but i don't know if i have the money."

7:48 pm

he said, "i'm going to give it to you for practically nothing." so i said, "how much?" and he told me, i think, $40,000, $45,000 for that building. so i called up melzack in washington. i said, "i need $40,000. "do you really want that painting? i'll get it from max." melzack said, "well, milton, i don't know whether i can afford to buy a painting now." so i said, "okay," and i went to paint, and while i was painting, the telephone rang. and i said, "that's melzack, i know it is." so i got on the phone. he says, "i'll give you $30,000." so i says, "okay," and i bought that building. the whole thing opens up into a kind of growing field. now, feelings that are too strong are hopeless.

7:49 pm

you go mad. you say, "enough, goodbye!" ah! so there is a kind of artistic, maybe, feeling which is not too strong, not too weak, and it just seems as if you can put yourself up against it. you can almost push against that so that it's there for you. and if you sense that, then you don't have to see your painting anymore. if you put paint there, you're putting it into that feeling. ah! nobody i know has ever painted like that, but that's how i painted for the last 40, 50 years. ahhh! enough. [ sighs ]

7:50 pm

[ sighing ] ah! i'm tired. technique -- i have no technique. i'll tell you though, what it amounts to is, a painting has to be occupied. all the parts have to be active. it has to have feeling. now, this feeling doesn't have to be so physical, but it has to be as if i come at you, and you're suddenly frightened, or you have a glass, and there's something in it, and it's kind of a funny color, and someone says, "drink it." and you say, "what's in it?" and they say, "drink it." and you say, "but what's in it?" and they say, "if you don't drink it, i'll shoot you." so you have to drink it. so that's the feeling. i have to put paint on. that's the only way to work.

7:51 pm

you just put paint on and let paint do the talking. if you use a brush, you can use it any old way you want, you know. you can dip a whole bucket of paint on it and spread it all over. you can use it on the side, or you can wipe it, you know. i have lots of brushes, hundreds of brushes, and i don't clean them. you know, i just leave them around. after i stop painting, i just leave them. and they get a little stiff, and that becomes another character in the brush. and then you kind of stamp it into the carpet under your feet and loosen it up. and finally, when you look at the brush, it's covered with paint. you throw it away.

7:52 pm

this painting, somehow, i don't remember anymore. but it seemed that everything had disappeared at one time, but there was a space in the middle, and i thought i'd put a tree in the middle. and that's the worst place for a tree. i thought it would irritate me enough to put one there. you have to do something to yourself to overcome these feelings you have about a painting being right or wrong. you have to kill those ideas if you can. this painting had once upon a time

7:53 pm

been the only painting that was finished. and then because it was finished, i hated it because i can see i can do something else with it. to tell you the truth, all i like is that snake. that's it. trouble. trouble, trouble, trouble. so you can see that the figures and the trees and all the things that's supposed to tell you what the painting is all about, is not. it isn't really the painting. the painting is what paint does. and you have to be a kind of straw in the wind. you have to give in to what the master, paint, does in the picture. and you give in to it. you paint what it's telling you to do.

7:54 pm

man: people talk to us a great deal, and, you know, they come in steadily to see the work that you're doing and have been doing with images. and even once in a while, you know, somebody buys one. resnick: the paintings are really something i work on. and once i no longer work on them, they're not really the same thing. they look different. i don't think they're my paintings anymore.

7:55 pm

92 Views

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11